|

My Work As An Educator What I Teach, and Why I Teach How I Teach Beyond the Classroom How Who I Am Informs My Teaching

| |||

What I Teach, and Why I Teach

Facilitating intercultural exchange and creative dialogue with empathy and humility is the core of my practice as a set designer, and is the foundation of my work as an educator. I strive to foster ethical, energetic excellence in tomorrow’s storytellers, but I also strongly believe in the value of a theatrical education regardless of whether or not students eventually choose to pursue professional careers in the performing arts.

While I empower my university, high school, and middle school students with knowledge, skills, and experiential learning necessary for both artistic and professional success, it is most important that my students have practice building and maintaining spaces where they can express themselves- knowing that they will not always agree, but that they do always need to be able to reflect on an empirically explain their creative perspective to each other and to themselves.

No matter what a student's primary interest within the theatre might be, our work together encourages them to contextualize their individual practice. Every student is encouraged to develop their own unique creative process by engaging in:

I balance my current role as Special Visiting Faculty in Scenic Design at Carnegie Mellon University School of Drama alongside my work as an award-winning, nationally active scenic designer. Prior to joining CMU, I was an Assistant Professor of Theatre at Albright College, where I designed scenery for all Theatre department productions while teaching a wide range of courses, including: Theatre History, Senior Seminar, Case Studies in Contemporary Global Scenography, Design Fundamentals, Creative Process, and Independent Studies in Playwrighting, Dramaturgy, and Scenic Design. I was previously on faculty at Wake Forest University, and have taught, adjudicated, and led workshops around the country for institutions such as New York University Tisch School of the Arts, UT Texas Austin, the United States Institute for Theater Technology, the Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival, Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing Arts, the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center, and many others.

Facilitating intercultural exchange and creative dialogue with empathy and humility is the core of my practice as a set designer, and is the foundation of my work as an educator. I strive to foster ethical, energetic excellence in tomorrow’s storytellers, but I also strongly believe in the value of a theatrical education regardless of whether or not students eventually choose to pursue professional careers in the performing arts.

While I empower my university, high school, and middle school students with knowledge, skills, and experiential learning necessary for both artistic and professional success, it is most important that my students have practice building and maintaining spaces where they can express themselves- knowing that they will not always agree, but that they do always need to be able to reflect on an empirically explain their creative perspective to each other and to themselves.

No matter what a student's primary interest within the theatre might be, our work together encourages them to contextualize their individual practice. Every student is encouraged to develop their own unique creative process by engaging in:

- rigorous exercises in critical research and analysis

- building verbal, physical, and visual vocabulary for effective communication and collaboration

- identifying strategies for both self-assessment and collaborative assessment

I balance my current role as Special Visiting Faculty in Scenic Design at Carnegie Mellon University School of Drama alongside my work as an award-winning, nationally active scenic designer. Prior to joining CMU, I was an Assistant Professor of Theatre at Albright College, where I designed scenery for all Theatre department productions while teaching a wide range of courses, including: Theatre History, Senior Seminar, Case Studies in Contemporary Global Scenography, Design Fundamentals, Creative Process, and Independent Studies in Playwrighting, Dramaturgy, and Scenic Design. I was previously on faculty at Wake Forest University, and have taught, adjudicated, and led workshops around the country for institutions such as New York University Tisch School of the Arts, UT Texas Austin, the United States Institute for Theater Technology, the Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival, Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing Arts, the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center, and many others.

How I Teach

As I work with my students to develop their individual artistic identities and powers of expression, I strive to balance this inward-looking exploration with rigorous exercises in outward looking and listening. This happens in the classroom through student-centered learning emphasizing formative assessment and guided peer evaluation, and outside the classroom through production work and independent projects with students.

Building a Shared Understanding of Learning Objectives, and a Common Vocabulary

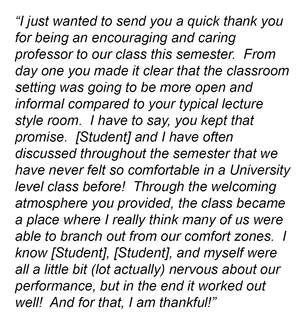

Students in my courses at Albright College participate in the creation of the syllabi and in selecting content. For example, prior to the start of the course, I sent the students in my Senior Seminar in Theatre a survey that asked both what they understood the objectives of this course to be- and what they thought the goals of the course should be. From there, they were asked to rank the value of various topics and projects we might cover in the course and suggest other avenues of exploration. While I did stipulate that we would be exploring work by Black playwrights and curated a shortlist of titles for consideration, I made sure to give students as wide a range of easily accessible choice as possible.

This groundwork allowed me to find connection points between course objectives, student interests, and student needs. Class sessions were structured to expand this understanding of everyone’s strengths, interests, and learning goals to the whole group, and encouraged students to learn from each other.

Senior Seminar, and indeed all my courses, are structured to build a collaborative, collectively-evolving cohort of students that will hopefully forget I am even in the room by the time the semester is over!

Articulating shared goals and the paths to realizing these goals requires either building a shared vocabulary or identifying existing common ground. At Albright, this led to me to create a Style Guide for the department that is now used in all of our courses. The document clarifies not only the conventions we expect students to follow in their writing, but also includes a glossary of terminology.

While I am passionate about equipping students with tools that are accessible and equitable, building shared vocabulary means that I must learn from the students in turn. One of the courses I enjoyed teaching the most at Wake Forest University was a compressed summer Introduction to Theatre class for incoming freshmen athletes. The class was both their first college-level course and their first theatre course, and they admitted that they were being forced to take it. Taking the time to build common ground allowed me to find points of access for them into the work.

For example, to explain the concepts of given circumstances and playable objectives, I asked the group of young men to all exit the classroom and re-enter with relatable scenarios and sets of objectives: “Walk back in like the opposing team is sitting on one side of the classroom, and you want them to be very, very nervous about the game this afternoon.” “It’s the first day of class. You know you are going to miss a lot of school going to away games, so you have to convince the professor and your peers that you are going to be the most dedicated student of the semester. How do you walk in? How do you sit down?” They unpacked their focus, body language, and the responses they each had to their peers’ choices; this exercise grounded subsequent analyses of performance.

Multi-Modal Learning

Pre-Covid, incorporating multi-modal and remedial learning into my courses at Albright was as important as equipping students with discipline-specific knowledge and skills. This continues to be the case as I create remote experiences for my students, while also considering the enormous mental, emotional, and material challenges they have been facing.

Course content is delivered in at least two modes; for example, play texts are accompanied by an audio or film performance recording, and podcasts are accompanied by transcripts. Similarly, assignments over the course of one class will provide opportunities for visual, aural, verbal, and kinesthetic learners to synthesize the material according to their strengths. For example, if the students are assigned to watch a documentary film, their engagement with it is evaluated not solely by their written responses or subsequent class discussion, but by both. I also include the estimated time commitment each assignment will require. This practice certainly helps students, but it also helps me confirm that I am assigning an appropriate amount of engaging, fruitful work.

Students create and receive feedback through guided peer evaluation (in large groups, small groups, and pairs), in writing, and in individual meetings with me where I will ask them to take their own notes of our conversation. No matter what form the feedback takes, I model and encourage students to avoid value judgements or even statement responses in favor of asking questions of and about the work- and more importantly the process of creating the work. Regardless of whether a course has been in-person or online, I facilitate open discussion of process by creating shared digital spaces for students that serve the same purpose as a shared physical studio- a space where students can observe and discuss each others’ work in progress.

Pre-Covid, incorporating multi-modal and remedial learning into my courses at Albright was as important as equipping students with discipline-specific knowledge and skills. This continues to be the case as I create remote experiences for my students, while also considering the enormous mental, emotional, and material challenges they have been facing.

Course content is delivered in at least two modes; for example, play texts are accompanied by an audio or film performance recording, and podcasts are accompanied by transcripts. Similarly, assignments over the course of one class will provide opportunities for visual, aural, verbal, and kinesthetic learners to synthesize the material according to their strengths. For example, if the students are assigned to watch a documentary film, their engagement with it is evaluated not solely by their written responses or subsequent class discussion, but by both. I also include the estimated time commitment each assignment will require. This practice certainly helps students, but it also helps me confirm that I am assigning an appropriate amount of engaging, fruitful work.

Students create and receive feedback through guided peer evaluation (in large groups, small groups, and pairs), in writing, and in individual meetings with me where I will ask them to take their own notes of our conversation. No matter what form the feedback takes, I model and encourage students to avoid value judgements or even statement responses in favor of asking questions of and about the work- and more importantly the process of creating the work. Regardless of whether a course has been in-person or online, I facilitate open discussion of process by creating shared digital spaces for students that serve the same purpose as a shared physical studio- a space where students can observe and discuss each others’ work in progress.

Student-Centered Learning

Wake Forest University's Introduction to Theatre rubric includes creative, production-oriented group projects. In lieu of assigning identical projects and deliverables to each group, I sent out an online survey to each student that asked what area of production they were most interested in exploring, presented several different project options, and provided the opportunity to suggest other project formats. I then put together teams of students with complementary interests and learning objectives. The semester culminated in a dynamic range of work that took their academic study of theatre and put it on its feet. One group pulled text from Fences and Death of a Salesman to create and stage a bus-stop conversation between Cory and Biff. Another group chose to focus on production design, and the four theatre novices conceived a 1920s gangster-land Hamlet. The dedication and enthusiasm these students, none of whom were Theatre majors, demonstrated in these projects came by allowing them to pursue individual lines of inquiry through their collaborative work.

Similarly, the majority of class presentations and discussions in my Theatre History class at Albright College are created and moderated by students. Each group delves deeply into one play; while I offer a list of areas they must cover as part of their presentations to build effectively on previous class discussions and make sure critical material is covered, I make room for suggestions and/or open time to contemplate what about the play is of particular interest to them. The students are evaluated not only on their grasp and presentation of the material, but also on their questions and discussion points for the rest of the class. The depth of the conversation that their analysis of the play encourages is as important as the analysis itself.

Wake Forest University's Introduction to Theatre rubric includes creative, production-oriented group projects. In lieu of assigning identical projects and deliverables to each group, I sent out an online survey to each student that asked what area of production they were most interested in exploring, presented several different project options, and provided the opportunity to suggest other project formats. I then put together teams of students with complementary interests and learning objectives. The semester culminated in a dynamic range of work that took their academic study of theatre and put it on its feet. One group pulled text from Fences and Death of a Salesman to create and stage a bus-stop conversation between Cory and Biff. Another group chose to focus on production design, and the four theatre novices conceived a 1920s gangster-land Hamlet. The dedication and enthusiasm these students, none of whom were Theatre majors, demonstrated in these projects came by allowing them to pursue individual lines of inquiry through their collaborative work.

Similarly, the majority of class presentations and discussions in my Theatre History class at Albright College are created and moderated by students. Each group delves deeply into one play; while I offer a list of areas they must cover as part of their presentations to build effectively on previous class discussions and make sure critical material is covered, I make room for suggestions and/or open time to contemplate what about the play is of particular interest to them. The students are evaluated not only on their grasp and presentation of the material, but also on their questions and discussion points for the rest of the class. The depth of the conversation that their analysis of the play encourages is as important as the analysis itself.

Formative Assessment

My scenic painting and set design students came to the courses with a range of experience and skills sets; because it did not make sense to evaluate their assignments relative to each other, my assessment of their work was based on their progress towards their individual learning objectives. We arrived at and articulated these goals through regular in-class discussion and feedback that I also distributed in writing. These hardcopy ‘dossiers’ were cumulative, meaning every time I handed back their feedback and grading for a project, the form also included grading and feedback for all previous work.

In this way for each assignment, every student must 1) explain, respond to and evaluate their work to the class, 2) give and receive constructive peer critique, 3) identify goals and strategies moving forward, and 4) contemplate each assignment in the context of their overall body of work in the course and their progress towards mastering specific skills.

My scenic painting and set design students came to the courses with a range of experience and skills sets; because it did not make sense to evaluate their assignments relative to each other, my assessment of their work was based on their progress towards their individual learning objectives. We arrived at and articulated these goals through regular in-class discussion and feedback that I also distributed in writing. These hardcopy ‘dossiers’ were cumulative, meaning every time I handed back their feedback and grading for a project, the form also included grading and feedback for all previous work.

In this way for each assignment, every student must 1) explain, respond to and evaluate their work to the class, 2) give and receive constructive peer critique, 3) identify goals and strategies moving forward, and 4) contemplate each assignment in the context of their overall body of work in the course and their progress towards mastering specific skills.

Inclusive Pedagogy

Albright’s diverse student body brings a wide range of strengths, learning styles, and learning goals to work beyond the classroom, and so I have also adopted a multi-modal, inclusive approach to the production and pre-production process of Romeo & Juliet, an audio-visual adaptation of the play I am directing and producing this Spring. Over the month of September, I hosted Zoom sessions every Sunday where I played an audio performance of part of the play while screen-sharing an annotated script, took a screen break, and then moderated a 30-minute discussion of the text with any students that were interested in participating. Students were also invited to respond to the play through digital collage and subsequent discussion in another live online session, and to submit written responses to larger thematic questions about the play.

This slow, deliberate scaffolding levelled the playing field for students when it came time to audition, and to apply for production positions- a process I created and am beta-testing in the hope of building a more transparent and inclusive process of assigning students to department production roles. I have also been able to take the students' responses to and questions about the play along with the larger learning objectives they shared in our sessions to create a process-oriented and community-driven framework for the production.

The extended conversations we have had around Romeo & Juliet have also been an opportunity to engage students in the difficult and complex work of de-colonizing the professional, artistic, and pedagogical practices in our department. Although I love Shakespeare with my whole heart, and have had success bringing around even the most reluctant of students to connect with the plays, centering Shakespeare as the pinnacle of dramatic literature is as deeply problematic as it is entrenched in our practice. I have been transparent with my students about my own learning journey as I have been unpacking my relationship to Shakespeare’s work and its place in our history and canon, and they have been honest and transparent about their own experiences with the work in return.

As an educator, accepting my own ignorance has made me a more careful listener, and I would like to think that this is just as critical a skill as delivering a compelling lecture or a stimulating syllabus. I believe that learning goes both ways, both inside and outside the classroom, and that my responsibility as an educator is not to model “best practices” as much as curiosity, humility, and continually evolving practices.

I am fortunate to have relationships with colleagues at Albright and beyond that have been wonderful conversation partners as I have been considering how I can continue to grow and support equitable, anti-racist practices. Last semester, I presented an overview of the various ways theatre companies choose the titles that will make up a coming season at our weekly department Common Hour, which all theater students are required to attend. This sparked a larger conversation about involving students more closely in season selection.

After consulting with colleagues at nine different colleges, universities, theatres, and professional organizations, I am spearheading the next six weeks of Common Hour alongside department faculty to both model and collectively assess a new, more transparent and collaborative process of title assessment and season selection at Albright. The title assessment survey I have created is as much a teaching tool as a practical one, and I am looking forward to student feedback on the content and form.

Indeed, I have had the opportunity to learn as much from my students as I have from professional and teaching colleagues. In my Introduction to Theatre class at Wake Forest that was comprised entirely of incoming freshman athletes, the first play we explored together was Fences. When we watched contrasting performances by James Earl Jones and Denzel Washington in the role of Troy, I expected the students to immediately attribute the differences in their acting to Jones’ imposing physique and Washington’s relative slightness. Instead, one student immediately said of Washington’s humorous Broadway turn: “That happened recently? I bet that if that audience is all rich white people, none of them want to watch an angry black man.” This insightful comment has continued to stay with me, even several years later.

There were many more moments of shared learning, most of which were empowering for the students, and many of which were also uncomfortable. They debated the inherent elitism of attending the theatre and the notion of athletics as theatrical performance. They listened and responded to one student’s discomfort with homosexuality while exploring Angels in America. They tried with all their might to convince me that Drake is the new Shakespeare (I remain skeptical). These students walked away with theatrical knowledge. But more importantly, whether we are in a dramatic literature, design, production, or performance course, my students learn that “I couldn’t relate to the play” is the start of the conversation, not the end. These conversations are the heart of the collaborative world-building.

Making Connections

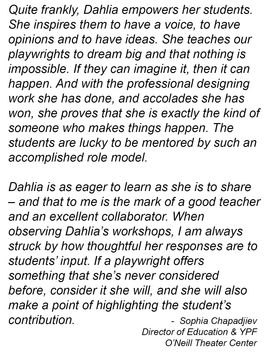

In workshops with middle school and high school playwrights at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, I designed an exercise that encouraged students to use their verbal skills as a vehicle towards understanding the visual elements of design. In one session, I distributed copies of a text and asked each student to come up with a list of adjectives, verbs and nouns to describe the scene and its setting. They then set the passage aside, and sifted through almost 500 images to find two pictures that matched each word on their list.

By breaking up their analyses of the text in this way, the students were able to confidently and methodically employ their verbal skills to analyze and respond to visual imagery. As a group, they discussed the reasoning behind their choices, and attempted to pick out which image in each pair was the strongest embodiment of the word; the comparative aspect of this exercise made articulating visual ideas more manageable.

Students learned that between two equally interesting interpretations there are very few “wrong” answers in this kind of work, only different choices. These young writers walked away with vocabulary for discussing visual ideas and connecting them to a text, and an awareness of their ability to shape how the world of their plays might look and feel in the hands of directors and designers. The ability to engage with work from multiple perspectives is the cornerstone of my work as an artist and educator.

In workshops with middle school and high school playwrights at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, I designed an exercise that encouraged students to use their verbal skills as a vehicle towards understanding the visual elements of design. In one session, I distributed copies of a text and asked each student to come up with a list of adjectives, verbs and nouns to describe the scene and its setting. They then set the passage aside, and sifted through almost 500 images to find two pictures that matched each word on their list.

By breaking up their analyses of the text in this way, the students were able to confidently and methodically employ their verbal skills to analyze and respond to visual imagery. As a group, they discussed the reasoning behind their choices, and attempted to pick out which image in each pair was the strongest embodiment of the word; the comparative aspect of this exercise made articulating visual ideas more manageable.

Students learned that between two equally interesting interpretations there are very few “wrong” answers in this kind of work, only different choices. These young writers walked away with vocabulary for discussing visual ideas and connecting them to a text, and an awareness of their ability to shape how the world of their plays might look and feel in the hands of directors and designers. The ability to engage with work from multiple perspectives is the cornerstone of my work as an artist and educator.

The End is the Beginning

A question I ask often ask in my courses is, “Why did I make you do this?” I have students answer this question for themselves and for each other partly to evaluate whether I have clearly met the learning outcomes for students with the assignment, but more importantly to encourage the students to contextualize a single assignment within the course as a whole and as part of their individual learning journeys. Arriving at their own understanding of how and why the assignment serves them means that students will be more likely to reflect on the process of completing the assignment and apply what they learned to subsequent work.

A prompt I learned from a mentor at Carnegie Mellon that I also often ask my students is, “If you had one more week to work on this, what would you do with that time?” Their answers often become or inform their goals for subsequent assignments, and helps turn any defeat they may have felt at the end of a project that went poorly into an action item. This is one of several tactics I use to frame the end of each project as a beginning.

The end of the course itself is also a beginning. Whenever possible, I create my own course evaluations to supplement the institution’s, and make time to discuss the questions with students class before asking them to complete a digital form. Both the conversation and the documentation encourage students to articulate their successes and areas for growth for themselves as individuals and as a collective, and to ponder the ways that the end of the course has equipped them for a new beginning. These documents also provide information critical to improving the course, and equip me for a new beginning as well.

A question I ask often ask in my courses is, “Why did I make you do this?” I have students answer this question for themselves and for each other partly to evaluate whether I have clearly met the learning outcomes for students with the assignment, but more importantly to encourage the students to contextualize a single assignment within the course as a whole and as part of their individual learning journeys. Arriving at their own understanding of how and why the assignment serves them means that students will be more likely to reflect on the process of completing the assignment and apply what they learned to subsequent work.

A prompt I learned from a mentor at Carnegie Mellon that I also often ask my students is, “If you had one more week to work on this, what would you do with that time?” Their answers often become or inform their goals for subsequent assignments, and helps turn any defeat they may have felt at the end of a project that went poorly into an action item. This is one of several tactics I use to frame the end of each project as a beginning.

The end of the course itself is also a beginning. Whenever possible, I create my own course evaluations to supplement the institution’s, and make time to discuss the questions with students class before asking them to complete a digital form. Both the conversation and the documentation encourage students to articulate their successes and areas for growth for themselves as individuals and as a collective, and to ponder the ways that the end of the course has equipped them for a new beginning. These documents also provide information critical to improving the course, and equip me for a new beginning as well.

Beyond the Classroom

The success of my work in the classroom and for the stage is built on community. Covid-19 has made this year a challenging time to maintain existing relationships let alone build new connections, but it is both possible and imperative. The Romeo & Juliet project that I am directing/producing is geared towards precisely this goal by directing the energy students would otherwise be putting towards building scenery, sewing costumes, or hanging lights towards community outreach and audience engagement. Their work this semester will lay the groundwork to be able to continue these efforts after we return to producing live theatre. Furthermore, because we are specifically focused on building community partnerships with high schools, this production work also supports our recruiting efforts and promotes our program.

As someone who grew up with limited access to books in a country with heavy media censorship, I am a passionate advocate for equitable, inclusive, accessible library and educational resources. In a digital world increasingly saturated with disinformation, it is particularly critical that we build students’ information literacy. When I became aware of an existing Information Literacy Survey that was being administered to first years, I contact Albright’s Associate Library Director and asked for access so that I could offer it to my Senior Seminar students. After administering the survey, I discovered that there were flaws in the design that made data collection cumbersome, and that there was a missed opportunity to use this not just as a data gathering tool, but as a teaching and evaluation tool.

I created a new version of the survey for the Library to review that demonstrates the wider uses of their survey, and how data collection can be both easier and more useful, with an accompanying explanation of how and why I had made the suggested changes that I did. This has prompted a larger discussion among the librarians about how they both teach and evaluate information literacy, and I hope to continue to work with them to find ways increase both information literacy and community use and support of our library.

My background has given me the privilege of being able to move through both White and Global Majority spaces with relative ease, and I have embraced the responsibility that entails both within my department and in my work with the wider community. This year after participating in a three-day workshop- Whites Confronting Racism- I left with immediate action items. I have made sure that at least 50% of the work I cover in my courses are by/for BIPOC artists, and the majority of images in my presentations and teaching materials are of BIPOC, disabled, and/or LGBTQI+ bodies. Meanwhile, my work with students and faculty in re-imagining our season selection process led me to center my introductory presentation to the students around questions of diversity and inclusion. The presentation included case studies in season selection from several different companies, the We See You WAT initiative, and Porsche McGovern’s ongoing assessment of gender equity, or the lack thereof, in the American theatre.

My ongoing journey towards becoming more anti-racist has been informed by my work on Albright’s Council for an Inclusive, Thriving, and Equitable Community. I am co-producing a three-part series for CITE-C, The African Roots of Western Culture, intended to challenge and broaden our campus' understanding of African civilizations, specifically examining the largely unacknowledged cultural debt the Western world owes to the continent. I am “leading” our first session, in which we will be watching and discussing the first episode of the PBS documentary series Africa’s Great Civilizations. I am not positioning myself as an expert, but as a fellow learner and conversation facilitator, and I hope that this will foster a safe space for discussion.

My time at Wake Forest University prepared me for my current endeavors at Albright. At Wake, I was actively involved in university-wide curriculum review focus groups. I participated in the long-term planning for integrating the art, music, dance and theatre departments; facilitated the creation of new branding, marketing and recruiting materials for the Theatre and Dance Department; recruited students both on campus and nationally; and fostered relationships with other departments through interdisciplinary and intercultural projects like the DACA playreading I produced and directed. In greater Winston-Salem, I supported local theater by connecting students with opportunities to both hone their skills and contribute to their community. I continue to look for professional opportunities for my students at Albright as I design scenery for regional theaters such as the Dallas Theater Center and Trinity Rep, and while supporting tomorrow's storytellers through workshops at various institutions, including the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center, NYU, UPenn, and UT Austin.

|

How Who I Am Informs How I Teach Both my pedagogy and creative practice are shaped by my multi-national background. Over 80% of the population of the city I grew up in were foreign expatriates, so it was a given that the majority of the people I came into contact with every day would come from vastly different cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. Rarely did anyone have a “typical” story. Since moving to the US, I have frequently found myself challenging stereotypes and preconceived notions. It can be easy for others to make assumptions about me based on very little- I speak with an American accent, I have my white mother’s coloring, and I attended Wellesley College and Carnegie Mellon. These facts often lead to assumptions that are at odds with my truth, and so I work to avoid making my own assumptions about students or collaborators. I had never seen a stage production of a play prior to my first year of college. Had the faculty and students at my alma matter been less inclusive or supportive, I would not be practicing my craft. My own experience proves that everyone has a storyteller inside them. Theater can not exist without a fully present audience of careful watchers and listeners, and I think of my teaching practice as exactly that- serving as the audience for my students that makes the alchemy of their theater - of their self-actualization - possible. The greatest compliment I have received about my design work was and continues to be, "I look at all of your productions, and it is impossible to tell that this is all one designer." As I have developed a personal artistic practice separate from my work in theatre, I have come to approach my design process as an act of service that, while informed by my own aesthetic journey, is guided by the needs of the play and performers. Likewise, my teaching practice does not encourage students to adopt my process or aesthetic. The goal is not to make a student more like me. The goal is to empower the student become more themself. |